The idea of an archive is a recurring theme in my current practice which manifests itself into recent works. In particular, I have been curious to excavate my own digital collection of bytes and pixels as a way to discover anything that might evoke meaning or value within and beyond its original context. I attempt to consider digital files as material, whether in parts or as a whole, including images, texts and fragments that could be used to tell stories or ideas. I am interested in their potential as residual artefacts, records of a time organically engaged in a widespread informal accumulation of information.

I sometimes refer to my process as an “archaeology” of sorts, echoing the same terminology prescribed by Michel Foucault to describe “the analysis of the archive” in his book The Archaeology of Knowledge (London: Tavistock Publications, 1972; translated into English by Alan Sheridan Smith).

Foucault speaks about the archive within a formal system that manages the creation of historical records for a society, specifically as curated “statements” of a recognised past. Yet he also began to acknowledge the existence of multiple versions of this system that may run concurrently across different contexts, which by extension allows for the study of other forms of archive beyond prescribed structures. It is in this vein that I begin to consider the potential of digital accumulations as informal archives.

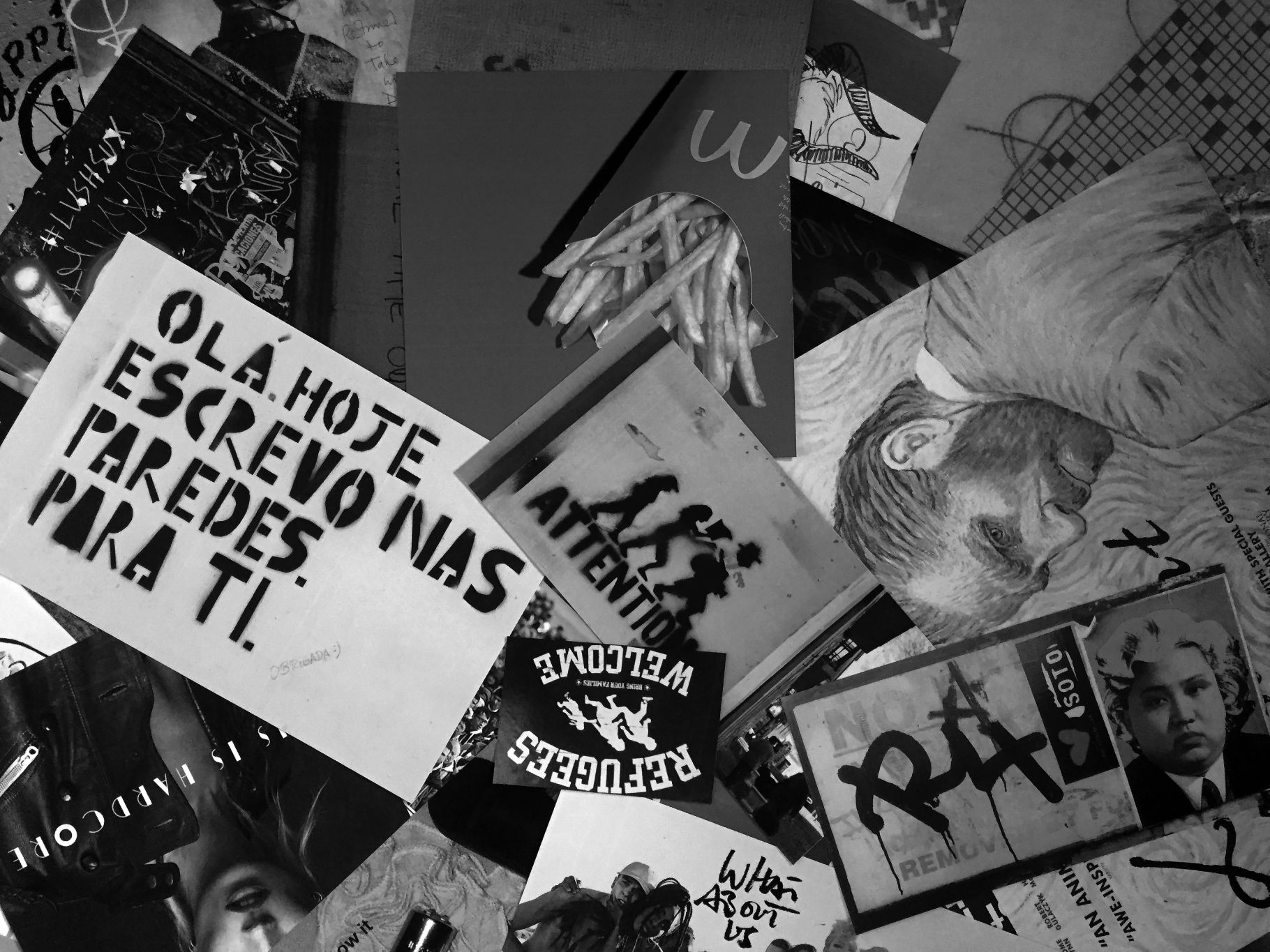

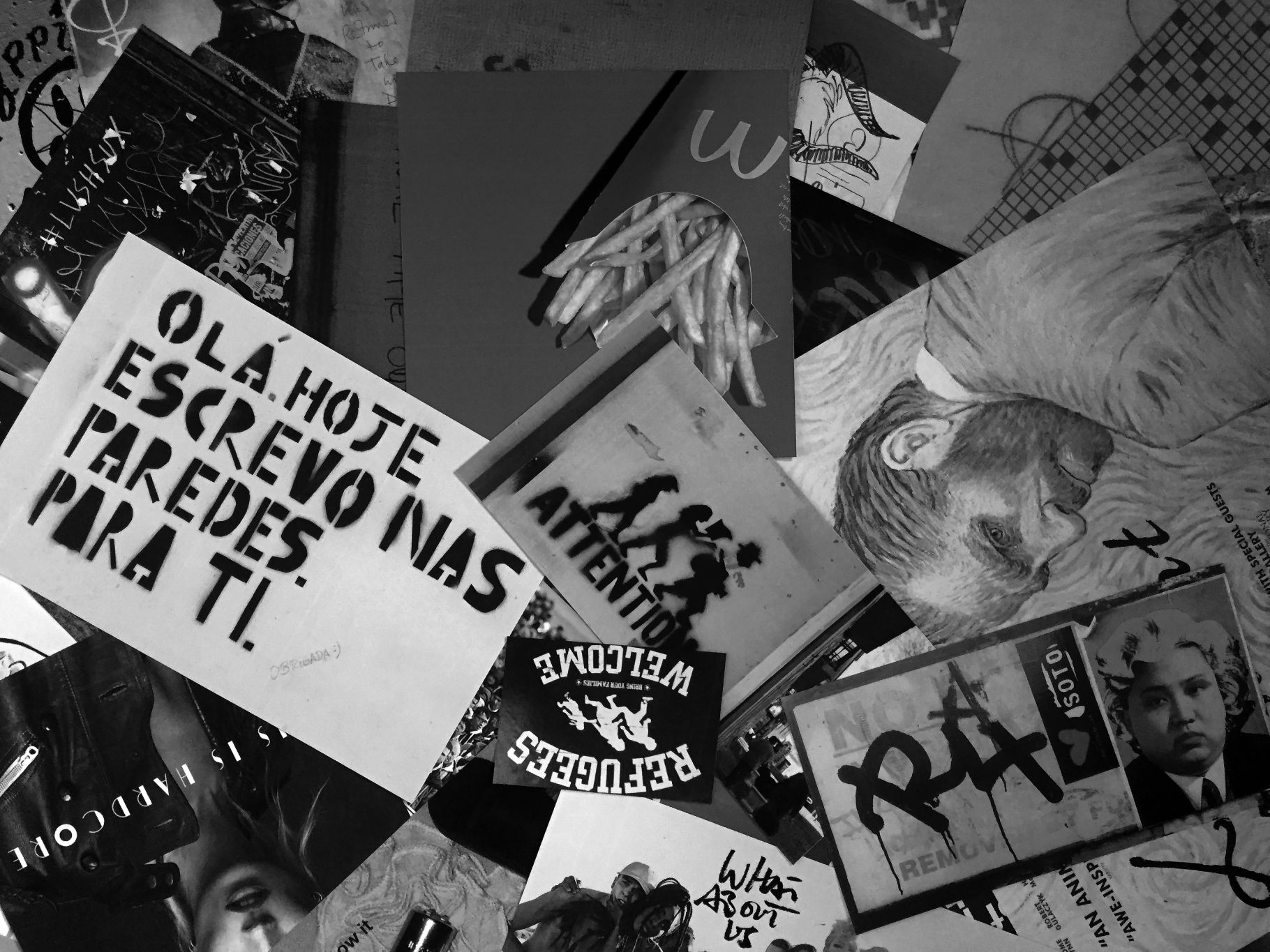

My own personal digital archive is my starting point in this process. While surveying my digital files for a book project, sifting through various devices, external hard drives and the cloud for images of graffiti (some of which can be seen in the image above), I began to notice the sheer amount of electronic assets I have accumulated over the years. I have, for instance, approximately 25,000 files in the cloud alone, records ranging from personal activities to professional work.

Yet I am by no means unique. Most people in contemporary society are now engaged in this informal accumulation of digital material. Collectively, we may have reached a point of excessive activity that the concept of “digital pollution” has become a point of discussion as noted in a Forbes magazine article, “The Alarming Rise of Digital and Content Pollution” (March 2013).

The term “digital hoarding” has also been coined, as mentioned in a Washington Post article, “Just Say No to Digital Hoarding” (December 2014), and a Mashable piece, “Confessions of a Digital Hoarder” (February 2017). These portray the condition as the excessive acquisition of digital materials and a reluctance to delete anything that is no longer useful, a characterisation that many people today may fall into in some form or degree. And as such there is an opportunity here to consider these accumulations as materials unto themselves, exposing its contents and potentially revealing the symptoms of the desire to make and keep them.

Admittedly, there is perhaps an element of melancholy in this aspect of my practice, a process of bridging the gap between the past and the present. There is already a tradition in art relating to the archive in this way, such as the works of artists like Tacita Dean, whose practice involves archival research, often to redeem a past that has failed or have been lost in some way, manifested in pieces like Girl Stowaway (1994), which imagines the journey of a person deduced from available records.

Hal Foster wrote about this process in his essay “An Archival Impulse” (2004), reprinted in The Archive (London: Whitechapel/Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006) from the Documents of Contemporary Art series, where he acknowledged the archive’s potential as a point of creation, rebirth, redemption, resolution or rediscovery:

“…its utopian ambition - its desire to turn belatedness into becomingness, to recoup failed visions in art, literature, philosophy, and everyday life into possible scenarios of alternative kinds of social relations, to transform the no-place of the archive into the no-place of utopia… to turn ‘excavation sites’ into ‘construction sites.’”

That said, my interest in the digital archive lies beyond the personal. As a keen observer, and some time documentarian of contemporary life, I am genuinely curious in its potential as artefacts waiting to be excavated and examined. I hope to continue my attempts to use them as materials in visualising stories and ideas that aim to encourage a reflection on our preoccupations, perceptions and memories.

It is important to note at this point that even with my humble efforts, archives - most of all informal accumulations - are inherently problematic sources of history and information. Foucault, going back to The Archeology of Knowledge, reminds us of its limitations:

“It is obvious that the archive of society, a culture or a civilisation cannot be described exhaustively; or even, no doubt, the archive of a whole period. On the other hand, it is not possible for us to describe our own archive, since it is from within these rules that we speak… The archive cannot be described in its totality; and in its presence it is unavoidable.”

Perhaps it is these “fragments, regions and levels” that I find alluring in my quest to explore the archive; the idea that these pieces may offer a glimpse of a past that is already slipping away, renewing them by the mere act of looking and remembering, and thus acknowledging, if not also extending, its existence. They have the potential to not only act as artefacts or records, but also as materials that can be reused, reconstructed or repurposed at any time, injecting life into something old within a new context.

There is also a struggle between keeping and discarding which further complicates the status of any archive. On one hand, the things we accumulate - consciously or otherwise - may prove useful in some way, while on the other hand, it may be better to let go, forget and start afresh. Andy Warhol demonstrated this contradiction in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (Harcourt Publishers, 1975) where he described his thought process in preparing his Time Capsules from 1974 onwards, boxes of random things he owned to be opened at a later time.

He said: “I really hate nostalgia, so deep down I hope they all get lost and I never have to look at them again. That’s another conflict. I want to throw things right out of the window as they are handed to me, but instead I say thank you and drop them into the box of the month. But my outlook is that I really do want to save things so they can be used again someday.”

He alluded to the psychological burden of material accumulation, referring to his closet as a “dump” that “drive you crazy.” He recommended adopting an “expiration date” so things can be thrown away, or even lost - “another load off your mind.” In the end, Warhol left behind 610 boxes from the last 13 years of his life, and the last intact box was opened in 2014. The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburg, USA now describes him as an “obsessive collector.”

I share Warhol’s internal conflict, but at this particular time my curiosity for the potential of the archive is greater than my desire to dispose them. Perhaps Jacques Derrida explained it best in Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (University of Chicago Press, 1996): “…we are all in need of archives… [as a] compulsive, repetitive and nostalgic desire… [for the] most archaic place of absolute beginning… searching for the archive right where it slips away.”

For me, they form traces of something - a moment, a memory, a person, a life, a history - often locked in a cycle of recording, storage and retrieval, swinging between disappearance and reappearance. It is important to remember and acknowledge the past through these residues, most of all because of the things we may learn from them.

In Perspectives: Negotiating the Archive (Tate Papers No. 9, Spring 2008) from Tate’s research journal, Sue Breakell, archivist and senior research fellow at the University of Brighton Design Archives, defined the archive as “a set of traces of actions, the records left by a life – drawing, writing, interacting with society on personal and formal levels.”

She added: “Archives are traces to which we respond; they are a reflection of ourselves, and our response to them says more about us than the archive itself. Any use of archives is a unique and unrepeatable journey. The archive is attractive territory for the exploration of critical theory because of the processes it both documents and enacts, its contradictions and discontinuities. It is also appealing because of the way it both seems to reflect ourselves and yet so clearly does not.”

While strict definitions of the term are often complicated and attitudes diverse, I recognise this version of the archive as applicable to my own interest in this subject, even though I am relatively in the early stages of this exploration. It remains as a recurring concern in my current practice, relating to a wider theme of traces, residues, fragments and accumulations.

Nevertheless, as I continue experimentations with methods and materials, I am interested to discover the different ways I could use digital files in various works with the hope of better developing ideas as I move forward. These works show the implications of time which on one hand function as a straightforward representation of what is often a natural cycle of changes, and on the other as a cautionary tale on how some things can be inadvertently lost or forgotten. It is up to each viewer to determine their own position within these landscapes.